“Attention is the rarest and purest form of generosity”

― Simone Weil

How often do we actually give someone our full attention?

You’re in the middle of an intense project. At work, at home. Your mind is on that project (Joe was supposed to send that last week!). At the same time, your mind is bouncing around among other ideas (Hubs stayed late at “work” again … is he having an affair?), other projects (can we afford to remodel the bathroom?), or obligations (gotta do the laundry tonight; Jenny’s soccer uniform is filthy), all in a conflicting swirl somewhere other than your current project.

Then someone wants to talk. Your teammate is struggling with his task. Your friend is dealing with a crisis. Your spouse approaches with barely suppressed anger. Your child is having trouble at school.

Oh, but that swirl of thoughts!! Can you put all those other thoughts aside and truly hear – and see – someone else, what they’re saying, what they’re feeling, what they’re really concerned about? Or is your mind thinking about your other challenges? Or are you busy composing what you’re going to say?

Talking “TO”

Are we only prepared to talk to someone? That’s a term almost everyone uses. “I liked talking to Peter at the party.” “I talked to my wife about that.” But what does that term really mean? Think about it. It sounds one-sided. If you talked to someone, what did they do? Did they talk? Did you listen, did you hear?

It seems to me that “attention” in human dialogue is a byproduct of differing objectives for, or approaches to, talking.

How Talking may or may not equal “Communication”

Years ago when I was COO in a high-tech startup, I attempted to train my Sales VP to ask questions of sales prospects, and listen. “You have one mouth and two ears. Use them in that proportion.” One day I took him to meet a prospective strategic alliance partner. As the meeting progressed, I asked questions such as “What would you expect to gain if we were to partner? How would you envision that working?” The prospect paused. I watched his wheels turn. I didn’t break eye contact. He was thinking. I saw it on his face. He was about to tell us exactly how our partnership could work, what he would agree to.

But pauses of silence can make some people uncomfortable. Especially salespeople. They must sell. My VP wasn’t paying attention to – “hearing” – what the man on the other side of the table was communicating in his body language and in the language of his silence. VP had to talk to – or more accurately, at – that person. He broke the silence, at the pivotal moment, with his sales pitch. The moment was gone. Lost. The prospect retreated, pulled back. Nodded in that dismissive way that says “Yeah, yeah, whatever,” and said something like “We’ll think about it and get back to you if we’re interested.”

My VP had tried to direct the conversation to where he wanted it to go (and probably wanted to show me he could close deals). If only he had allowed the prospect to voice his desires, his concerns, his goals, his ideas, the discussion could have proved fruitful for his company and for ours. But he felt pushed, cornered. Not heard.

Do Women Communicate better than Men?

Research has shown[1] that women’s dialogue differs from men’s in how they seek affinity and connection, asking questions of those listening to draw them into the conversation, more than men do. Yet it’s a mistake to assume that all women do that naturally. A young woman I know has social anxiety. She is extremely uncomfortable in large or small groups of people, especially those whom she doesn’t know. In those situations she freezes and retreats. Yet she desperately wants to connect with people, or at least not drive them away. When she is with just one or a few people, she tries to talk, to connect. But she also has Asperger’s, fueled by a brilliant mind filled with a wealth of knowledge. So she falls into the trap of talking to people, with an intensity in her voice that reflects her command of information. And her need to connect.

She’s now moving to a new city where she knows no one, to take a new job, where she knows none of her co-workers. She fully recognizes how her “neuroses” (her word) can turn people off, and worries that her mannerisms will annoy people. When she was in her teens I had shared a story (perhaps apocryphal) about a woman who was invited to a party where there were powerful people from all over the world, but the woman only understood English, not the languages they spoke. Her host dismissed her worry with “Just listen to them; you’ll learn a lot.” And so she did. Nodding, smiling, making eye contact, laughing at apparent humor, etc. The next day her friend called her and said “They all loved you! They thought you were a brilliant conversationalist!”

That story hadn’t helped the teenage version of my friend (or she hadn’t operationalized its lesson). So now as she contemplates her move, she’s worried that she will once again fail at conversation in her latest attempt at fitting into the world. I spoke with her about re-framing the idea of conversation. Rather than plunging into what is for her an agonizing prospect of talking to people, discard the concept of “to” – which suggests trying to get ideas across, impress people, tell them something. Instead consider talking with them, as a collaborative endeavor. I’m happy that she seemed energized by that idea, was able to connect with it, as if she’d just discovered a new portal to a different world.

Talking “TO” versus Talking “WITH”

The entire concept of human conversation could benefit from re-framing. The common idea of “talking to” someone doesn’t convey the idea of having a two-way conversation or discussion, and instead imposes the expectation – the burden – of telling something to another person. In many cases “talking to” devolves into “talking at” someone. No one is heard or understood.

If we can shift our concept of human dialogue to “talking with”, we achieve three major benefits:

- We relieve ourselves of the responsibility of ensuring the conversation is good or great. It becomes a shared venture in which two or more people engage.

- We avoid the need to impress or convince anyone of anything, certainly not of our own merit.

- We gain the opportunity to discover and learn about different ideas, experiences, adventures, and perspectives.

How can we accomplish all that?

Easy-peasy!

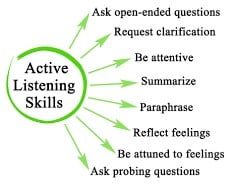

Relax. Simply ask questions. Listen to the other person. Hear what’s between their words ― their feelings, concerns, fears. Give them your full attention. Demonstrate that they and their thoughts are important. Of course this is similar to the practice of “active listening”[2] first discussed in 1957 by Carl Rogers. But it is easier, less pedantic, more natural – as day follows night – when we begin by clarifying our objectives in talking, what we want to achieve in our relationships with people.

Talking as a Partnership = Connection!

This way of re-framing the purpose and vector of talking WITH serves to establish the mode and expectations of interaction. We are engaging with other people by talking with them. It’s a partnership that allows us to set aside ego, as well as any obligation to impress people. It’s really about the other person:

Give that person your full attention. That is your gift.

The purest, most selfless form of generosity.

Your reward will be much greater than what you give.

[1] Psychology Today, December15, 2016 https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/blamestorming/201612/5-ways-men-and-women-talk-differently

[2] https://www.verywellmind.com/what-is-active-listening-3024343 February 13,